I had an experience I’ve never had before, and I hope never repeat it.

I recently got heckled during a talk.

Usually, I speak in spaces where the closest I get to “heckling” is a diocesan director of religious education yelling at the stage that I am talking too fast (this happened during a breakout for parish and diocesan leaders at the 10th National Eucharistic Congress) or a freshman in high school shining a laser pointer into my eyes during a youth rally (thanks, Owensboro, Kentucky).

But outright, antagonistic heckling? Never happened.

Until Tampa.

I was asked to be the keynote speaker for their pro-life rally, and I happily accepted. It is a vital task of Christians to uphold and protect the dignity of all human life. As I went through my notes the morning of the event, a thought crossed my mind: I wonder if anyone will come to protest?

It didn’t take long for my question to be answered.

Over a thousand people showed up to the church where the march began. Every seat was filled when I arrived, so I took my place in the back. It was a beautiful Mass, and I stepped out before everyone else after the final blessing to make my way to the park where the rally would be held.

I passed by a small group of three or four protestors.

As I walked onward, I saw another group of five or six approaching the start of the march. When this group arrived at the park, maybe ten were among the 1000+ pro-life marchers.

But a small number can be vocal.

For the most part, they stayed in the back of the crowd, but when I spoke, they moved and dispersed through the audience. At various points in my message, they played music on a speaker as a distraction, but I continued on—after all, it made a good soundtrack.

Then, near the end of the message, the shouting began. I was called some interesting names, but they are not worth repeating here.

It almost threw me off and could have derailed the message. This wasn’t a parish leader trying to be funny during a talk or an angsty teenager with a laser pointer. These were people who disagreed with my message – at best, they disliked me. That’s a different scenario.

There are moments we all face like this—moments of adversity that can trip us up and derail our progress. As I’ve reflected on my situation with the hecklers, I did a few things right, which allowed me to move forward and complete my talk the way I intended.

I’m writing them here so I can remember them for next time (it’s just as important, if not more important, to analyze our successes than our failures).

I acknowledged the distraction and obstacle internally but didn’t engage.

This is speaking 101: You can’t give power over to a disruptive member of the crowd unless you are fully prepared to fight down that pathway. Comedians often engage hecklers because they are disruptive in a small comedy club and usually make it a part of the show but at the expense of their set. They end up engaging with a heckler and either shut them down or encourage the behavior until the heckler is removed from the show (or leaves).

Anytime a speaker interrupts his or her content to engage with a disruptive member of the audience, the message suffers. I’ve not seen anyone outside of a comedy set do this well. The best way to deal with disruption is to acknowledge it is happening in your mind but not give the disruption power outside of it.

I would have been unsuccessful if I had tried to ignore the voices yelling at me. Instead, I recognized they were there and made an intentional choice to ignore them. Sure, I could have engaged them—there were 1000 people who had my back—but then the message would have been about the heckler, not what I prepared.

Obstacles and distractions in our work and ministry look a lot like hecklers. They beg for our attention and can be pretty rude. They take the form of small “urgent” projects, angry emails, or even our internal thoughts. If we go down these rabbit holes, we quickly get off message and off mission. Recognize the distraction, but don’t engage it.

2. I didn’t let the heckler influence my train of thought.

Ahead of the message, I had a moment where I thought about what I might change to better reach the protestors or even change their minds. What could I say that would impact them? I also thought about what I might say that they could record or take out of context—should I remove those pieces?

After mulling it over, I decided not to change anything, and that was the right decision.

In the face of adversity, there is a temptation to change our course in an effort to either “people please” or to avoid conflict. This can be devastating. We can’t make sweeping changes when we find ourselves in moments of adversity unless it is absolutely critical. Usually, we make these last-minute revisions to a plan when we are uncomfortable.

When you commit to a course of action in work and ministry, you need to continue forward even if people challenge you. Yes, we can listen to feedback (and, in humility, should), but we also can’t simply make changes to satisfy a group or make a course of action more palatable. Usually, the people we are trying to “make happy” still won’t be.

3. I didn’t take it personally.

Criticism is hard for me because I often conflate my work with my identity. I’m actively working to break this mindset, but it still creeps up on me. When the few protestors in the crowd began yelling some of their more “colorful” names at me, my initial reaction was to wrap up quickly, call an Uber, and get away fast.

“These people hate me,” was the last thought I had.

I went through a catastrophic sequence of events in my head in a matter of milliseconds:

They are going to take some video of this talk out of context and post it online.

It’s going to go viral.

A bunch of people I don’t know will say more terrible things.

I’m going to need to go into hiding and probably get fired from my job because of the controversy.

We won’t have any money and will need to go live with my in-laws in Philadelphia.

My life will be ruined.

Yeah, it was a big jump in a few short moments.

But then my new mindset kicked in: these people don’t even know you. They dislike your message, which is OK, but they do not know who you are. Don’t take it personally.

In the course of work and ministry, we need to make hard choices that people may not like. Sometimes, people make unfair assumptions about us and our intentions, especially if we are leaders. Don’t take it personally.

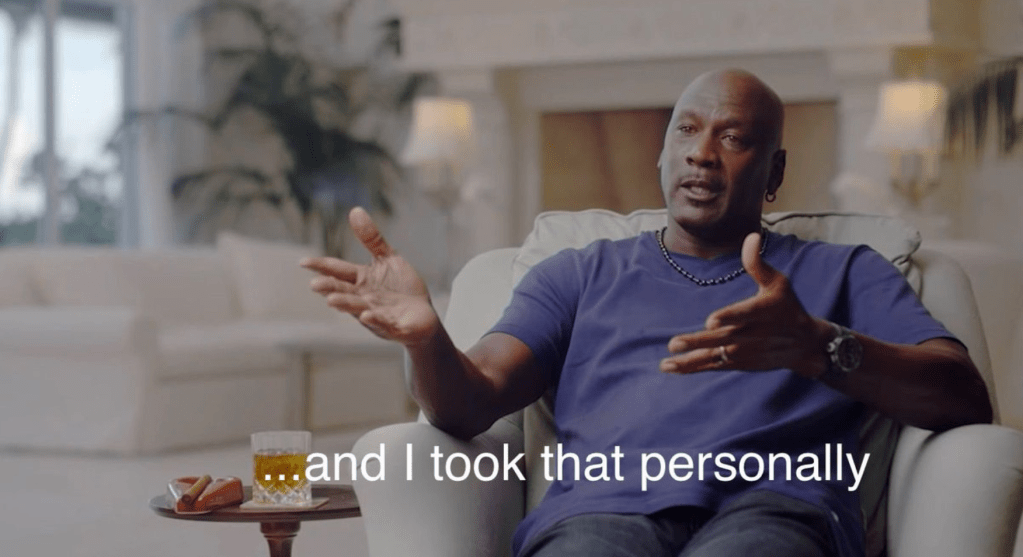

To be clear, taking it personally doesn’t mean that we become hurt and want to cry in a corner. Some people (who claim to not take things personally) become spiteful and vindictive. Think of Michael Jordan in the documentary “The Last Dance.”

If we take things personally, we will make things about ourselves rather than our message and mission. When we make things about ourselves, we quickly find ourselves off course.

When the event ended, people thanked me. I waited for one of the protestors and hecklers to approach me with a phone in an attempt to confront me for a social media post. It never happened, but it could have if I had confronted them publicly and given them the power. Maybe the message wouldn’t have been as well received by the people it was meant for if I made a bunch of changes last minute to try to appease a small group of ten people (who weren’t going to like it, regardless). If I had taken it personally, I would have missed all the fruit of the day because I would have been fixated on what a small group of people who don’t know me think about me (and they probably have forgotten about me already).

The next time I face a heckler (or a challenge), I will remember these three things; I got them right this time and want to repeat that success. Use them in your work and ministry—whether it is a kid with a laser pointer, a political protestor, or just an antagonistic team member in a staff meeting. You will navigate the situation with poise and confidence without compromising your message or mission, and that’s an experience worth repeating.

Leave a comment